|

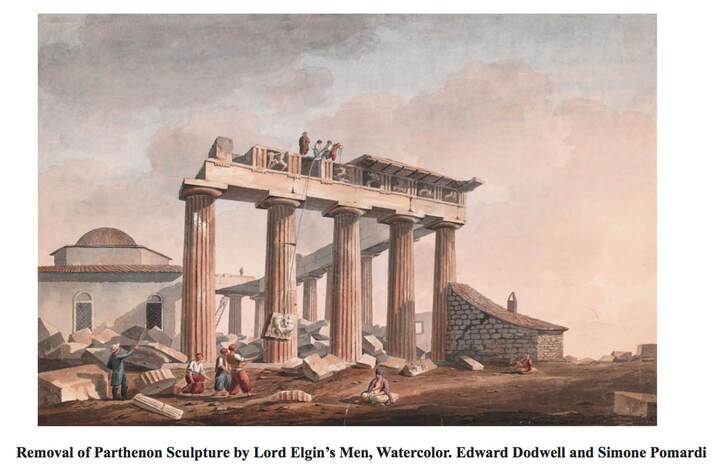

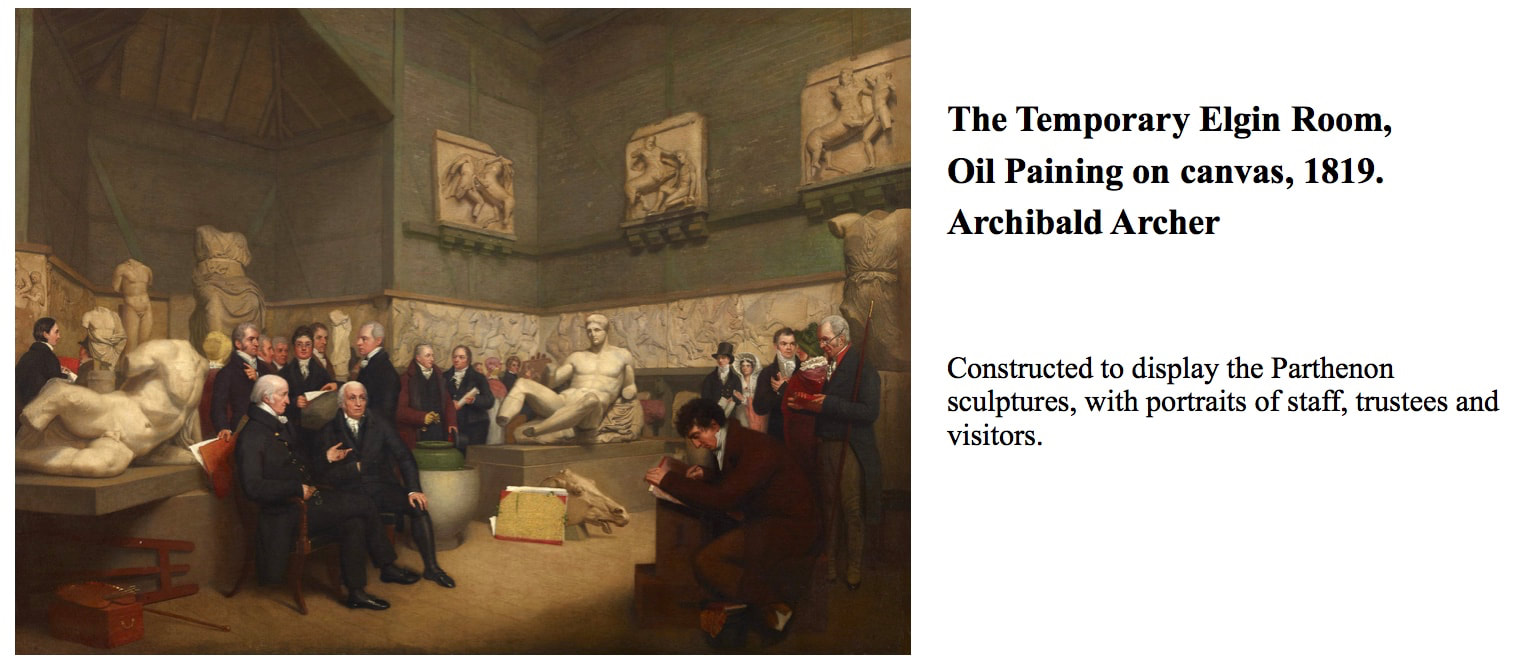

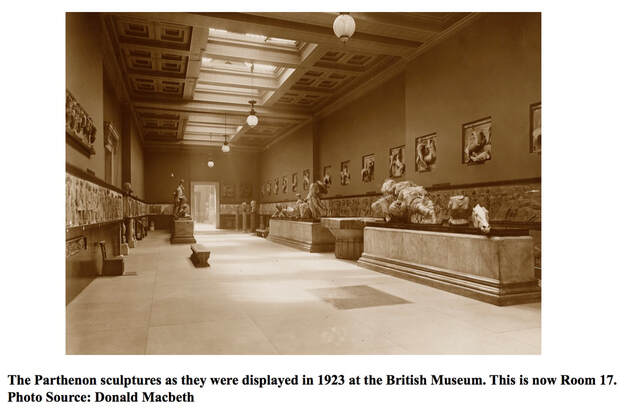

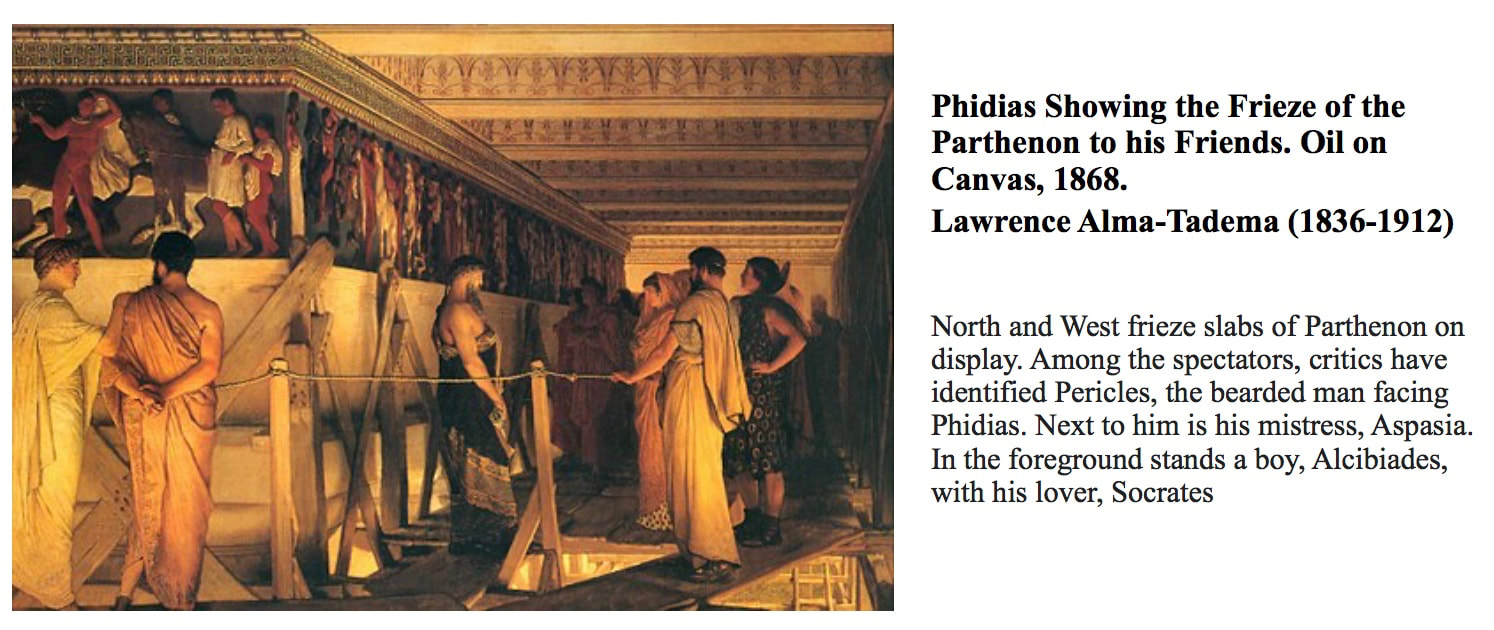

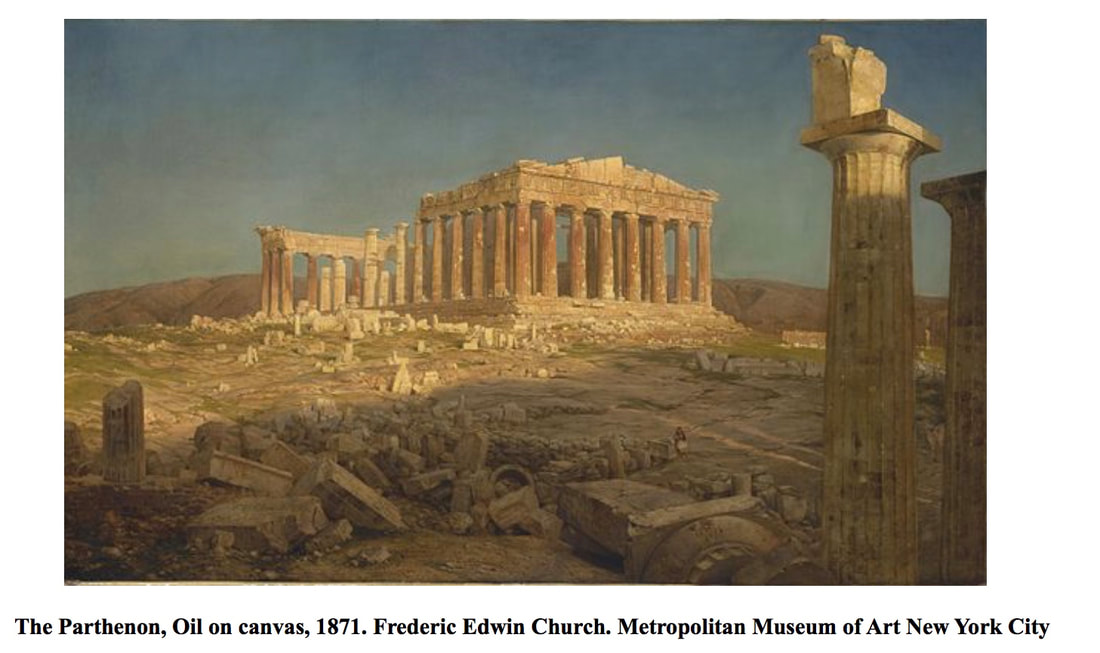

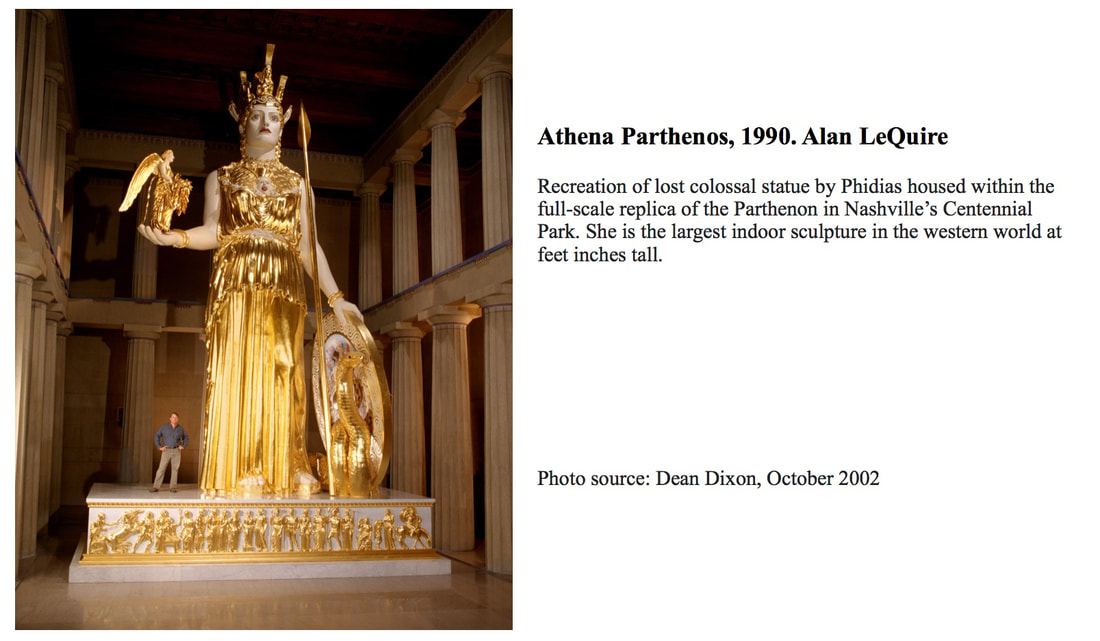

After the rediscovery of the Parthenon following years of neglect from an explosion during the Turco-Venetian War of 1687, British aristocrat Lord Elgin, appointed as British envoy to the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinope, instructed his agents in the removal of the building’s sculpture. Leaving behind the West section of the frieze, forty metopes on the northern, eastern and western sides, two free-standing figures on the West pediment and components unintentionally overlooked as they were buried deep beneath Acropolis bedrock. In 1816 due to sheer financial pressure, Elgin negotiated the sale of the Marbles to the British Parliament. Since the British museum’s acquisition of the sculptures, nearly 190 years ago, one of the world’s longest running debates has existed; whether the Elgin Marbles should be reunited with the remaining Parthenon sculptures at the Acropolis museum in Athens, Greece or should remain in the British Museum in London? The controversy resides in a contest between the universal and the local and the conflicting but “mirror-like” agendas of the opposing side.  The removal of the Parthenon sculpture by Lord Elgin in the early nineteenth century was undoubtedly vandalistic. The detachment of the frieze-blocks were impossible without first removing the cornices and other architecture elements responsible for holdings up the ceilings and roof of the Parthenon. Elgin was prepared to sacrifice these components with no hesitation, as he and his men resorted to the use of saws to gain access to the sculpture and reduce the weight of the sculpted blocks. They simply removed the cornice by dashing it to pieces, dropping the ruins to the ground below, leaving the remaining sculpture with greater exposure to the natural elements for the next two centuries. There is clear documentation that Lord Elgin’s motivations were purely self-serving, as he initially sought out the marbles to use as decoration for a Neo-Classical mansion he commissioned at the family seat at Broomhall in Fife. Only once the cost of transportation vastly exceeded Elgin’s expectations, did he negotiate the sell of the marbles to the British government in 1816. Although the legality of Elgin’s original acquisition of the Marbles is questionable, The British Museum has had valid legal ownership of the Marbles since Parliament’s purchase of them from Lord Elgin nearly 190 years ago, and the Museum has had no intentions of retuning them to Athens. Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum from 2002 to 2015 spoke of the equal division of the Parthenon Marbles between the Acropolis Museum in Athens and the British Museum as a ‘happy accident’ explaining, “They can be seen both in their Athens context and here, where they can be seen against the sweep of the whole of human history.. Each is valuable.”1 The main argument for keeping the Marbles in London is the benefits of having these treasures on display alongside works of other civilizations, exhibiting the sculptures in a context of world cultures, where millions of people and scholars can study and appreciate them. Claim to retention resides in the Marble’s central place in world culture. European Museums hold ‘an extraordinary repository of the high points of human achievement across many different cultures,’2 and before the marbles acquisition, greek sculpture was weakly represented in the British Museum’s collection. Current Director of the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer claims the Marbles as part of European history itself stating, ‘The rediscovery [of The Parthenon, 1687] is obviously part of European history.”3 Fischer believes The Parthenon ‘tells different stories’ which at various times throughout history served a variety of purposes such as a temple of Athena, a Christian church and a mosque, adding to the debate that the sculptures were no more made for the Acropolis Museum than they were for the British Museum. For the Greek and Roman Department of the British Museum, the marbles have become subject of detailed scholarly research embedded deep into British cultural consciousness and uprooting the Elgin Marbles would be devastating as the Trustees of the museum say the “marbles are the very jewel in their crown.”4 The repatriation of the Marbles would be robbing the British Museum and international publics of their display as a monument of Ancient Greece among universal world cultures. The conflicting but ‘mirror-like’ agenda of The Acropolis Museum, in Athens stresses the local over the universal as it is “the most natural understanding of the word ‘context’ in connection with the Marbles.”5 The main scholarly approach, for art historians and archaeologists alike, is to study the original context of deposition of an object, and investigate the original design as a whole. In the case of the Elgin Marbles that means reuniting the architecture of the Parthenon with its sculpture. The British Museum has taken steps in detaching the Marbles from their architectural setting by exhibiting the Marbles inside-out, disregarding their original context. Professor Mary Beard author of, ‘The Parthenon’ states, “The real trick of the arrangement is to present the Elgin Marbles as if they were a complete set... In order to bring this off, [the display] must effectively dismantle the original shape and layout of the sculpture as it was on the temple.”6 British press and public often refer to the marbles as “statues,” or independent works of art though this was not their intended purpose. The Marbles themselves were built into the Parthenon, not just as decoration, but functioned to keep the ceilings up. There are very few architectural components ripped from living buildings and exhibited in any other major Museum collection. Since the first recorded request for their return in 1835, the Greeks have contributed their feelings for the Parthenon to national identity and a majority of the Greek population share the hope of the Marbles return. The Parthenon is a national icon appearing on postage stamps, coins and currency. Primary school education includes lessons on the Parthenon and field trips to the Acropolis. The Greeks argument for the Marbles return centers on their place in the presentation of Greek history to their own public. More concerned with the actual pieces of stone, quarried just ten miles from Athens on Mount Pendell, than the cultural benefits of the prearranged ‘universal’ selection of civilizations on display at the British Museum.Which some see as a way of putting not only ancient but modern Greeks in their place. The Greeks would much rather take care of there own heritage, and believe the best solution is reunited the Marbles and exhibiting them in full view of the original Parthenon from the New Acropolis Museum, an ode to the Parthenon. The New Acropolis Museum founded in 2003 opened to the public in June 2008 and houses more than 4,250 objects found on the rock and surrounding slopes of Acropolis, Athens. Its top floor was designed to permit visitors the chance to view the Parthenon sculptures up close, against the backdrop of the Acropolis itself. On display is the remaining Parthenon architectural components and sculpture with blanks left for the missing Marbles. If returned the sculptures would be restored to their correct, outward-facing positions, reunited with the West Pediment. Greek President, Prokopis Pavlopoulos found an ally in its campaign to bring the Marbles home in President Xi Jinping, of China as they too have had pieces of artistic heritage fall into foreign hands.While touring the Acropolis Museum he made remarks in support of the Marbles repatriation. While some question the potential costs of moving the Marbles to Athens, Greeks would pay anything to get them back, the last Greek government offering to never ask for the return of anything else from Greek land in the British Museum. In 2018, The Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Country of Origin (ICPRCP) met at UNESCO headquarters in Paris and for the first time, released a statement taking a stance on the highly debated topic that acknowledged the arguments of both sides. The committee called on both side to “find a mutually acceptable solution to this long-standing issue.”7 In a 2019 interview with the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea, British Museum director Hartwig Fischer stated that ‘the government would have to rewrite laws in order to return the sculptures because their legal owners are the British Museum’s trustees.’8 There is currently no active discussion between the British Museum and Greek officials. I one hundred percent support the reunification of the Elgin Marbles with the Parthenon sculpture at the Acropolis Museum. Like most archaeologists and scholars I believe the study of an object’s original conception is most beneficial in understanding its original meaning. Having nearly all surviving artifacts in one location is crucial, especially the Elgin marbles, which served as architectural components built into the monument itself rather than detached works of art. The way in which the British Museum has arranged the Elgin Marbles is insulting to their original presentation and the argument of ‘universal’ reach is pointless if historically inaccurate, in which the display is. There has been a number of uncontroversial repatriations through history such as the fragment of Sphinx’s beard and the Stone of Scone, and pressure on museums to return artifacts acquired under colonial rule is increasing, including support of, Leader of UK’s Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn who promised to reunite the marbles if elected Prime Minister. Currently only one-quarter of the British Museum’s attendance includes the Marbles in their visit and opinion polls show 81% of the British population is in favor of the Marbles return. The majority of the British public, and possible elected officials understand the importance of returning theses treasures, so why are the trustees of the British Museum still holding them hostage? While researching this heated debate I kept in mind the three questions Tiffany Jenkins asks in, Keeping Their Marble, that should govern where significant artifacts should be kept, “What is best for the objects, for scholars and for the public? Where are they best cared for and displayed? How do they best serve the development of scholarly Knowledge and public interest?”9 The reunification of the Marbles to Athens is the answer to these questions, as it is the most historically accurate way of displaying the Parthenon sculpture, allowing for the study of its original conception in its intended context on the Acropolis. 1Snodgrass, A. (2004), “What do the Parthenon Sculptures embody? Working Papers in Art and Design 3”

2Earle, W. (2018) “Why the British Museum Should Keep the Elgin Marbles?” 3Rea, N. (2019), “The British Museum Says It Will Never Return the Elgin Marbles, Defending Their Removal as a ‘Creative Act’” 4Snodgrass, A. (2004), “What do the Parthenon Sculptures embody? Working Papers in Art and Design 3” 5Snodgrass, A. (1997), “THE ADVANTAGES OF REUNITING THE LONDON AND ATHENS MARBLES” 6”” 7 Ana, M. (2018), “UNESCO Committee Discusses Return of Parthenon Marbles in Paris” 8Rea, N. (2019), “The British Museum Says It Will Never Return the Elgin Marbles, Defending Their Removal as a ‘Creative Act’” 9Earle, W. (2018) “Why the British Museum Should Keep the Elgin Marbles?”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed