|

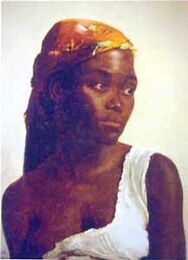

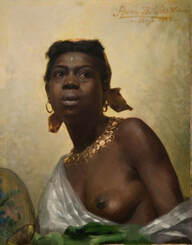

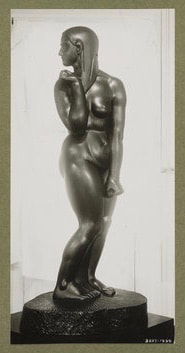

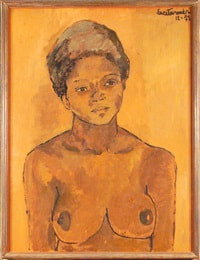

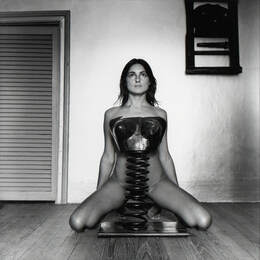

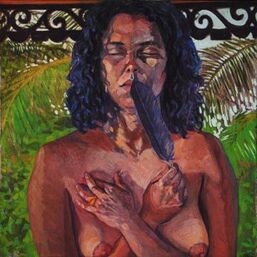

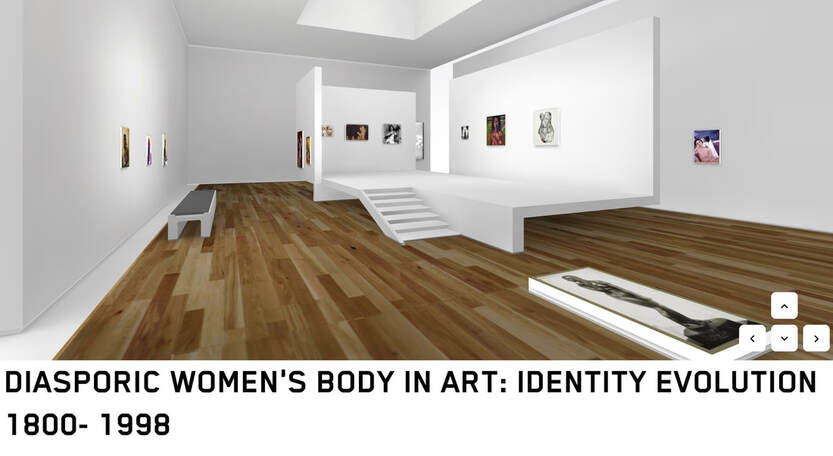

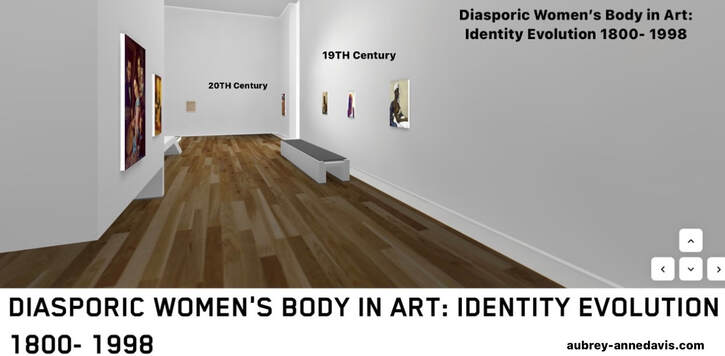

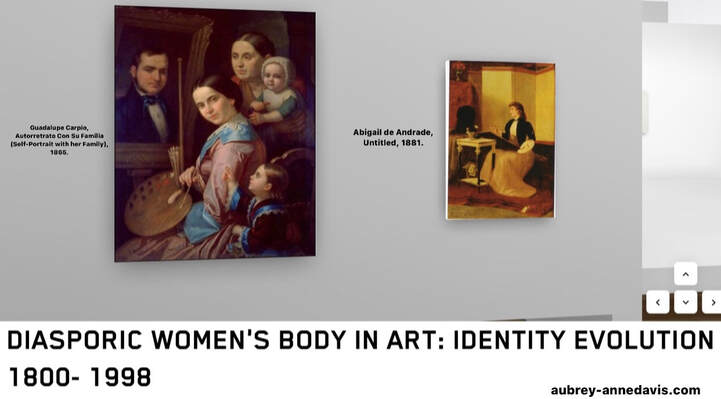

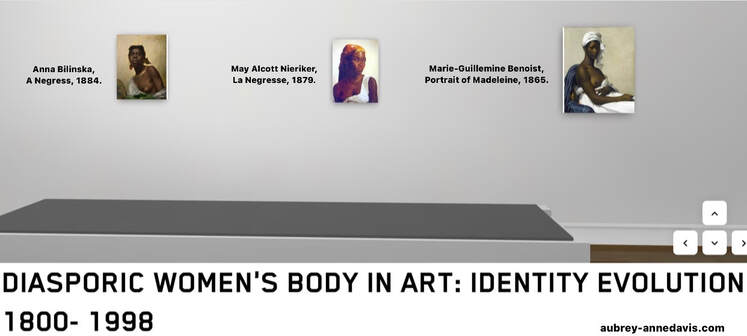

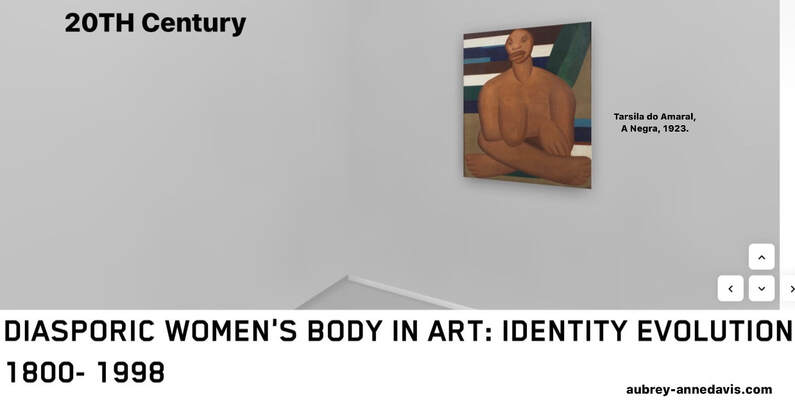

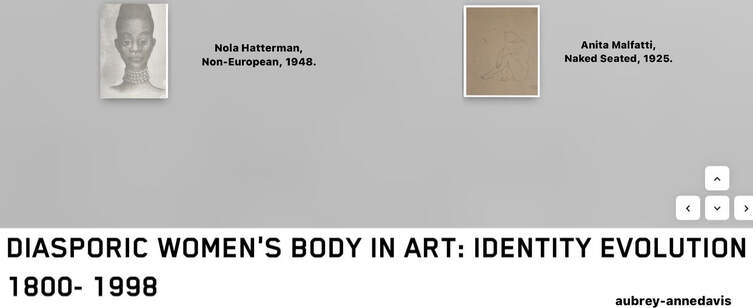

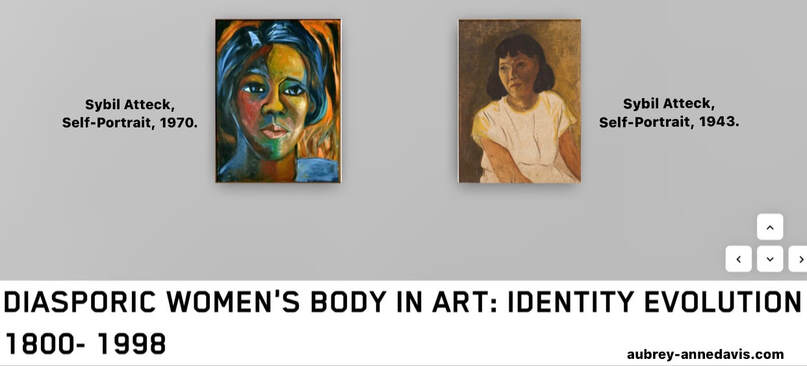

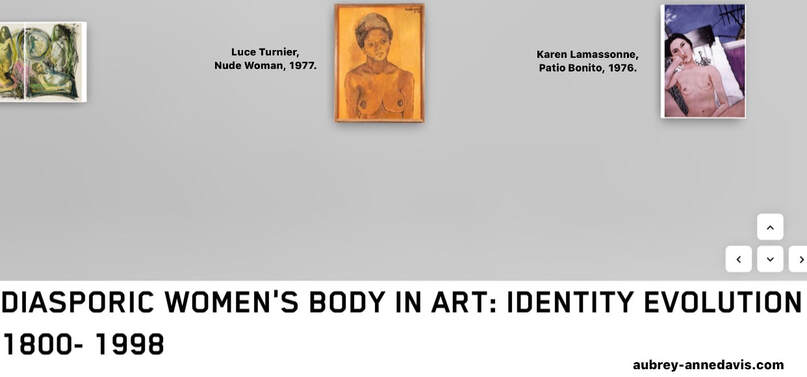

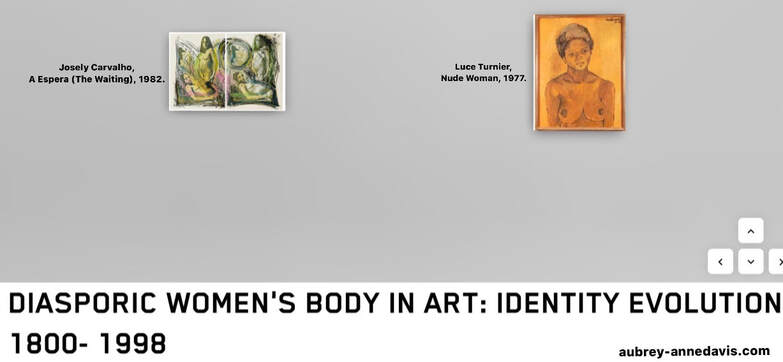

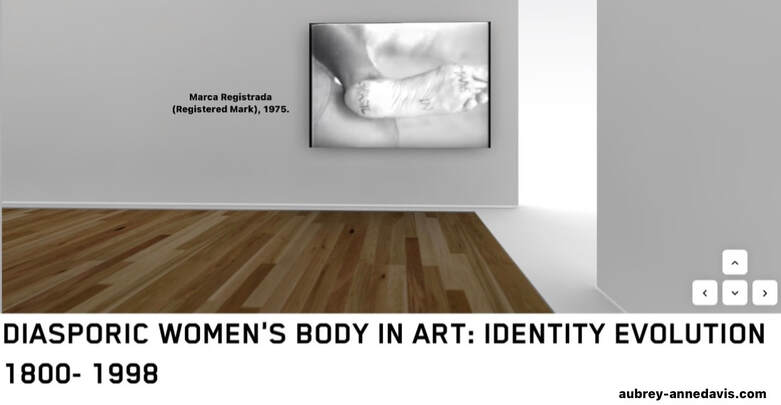

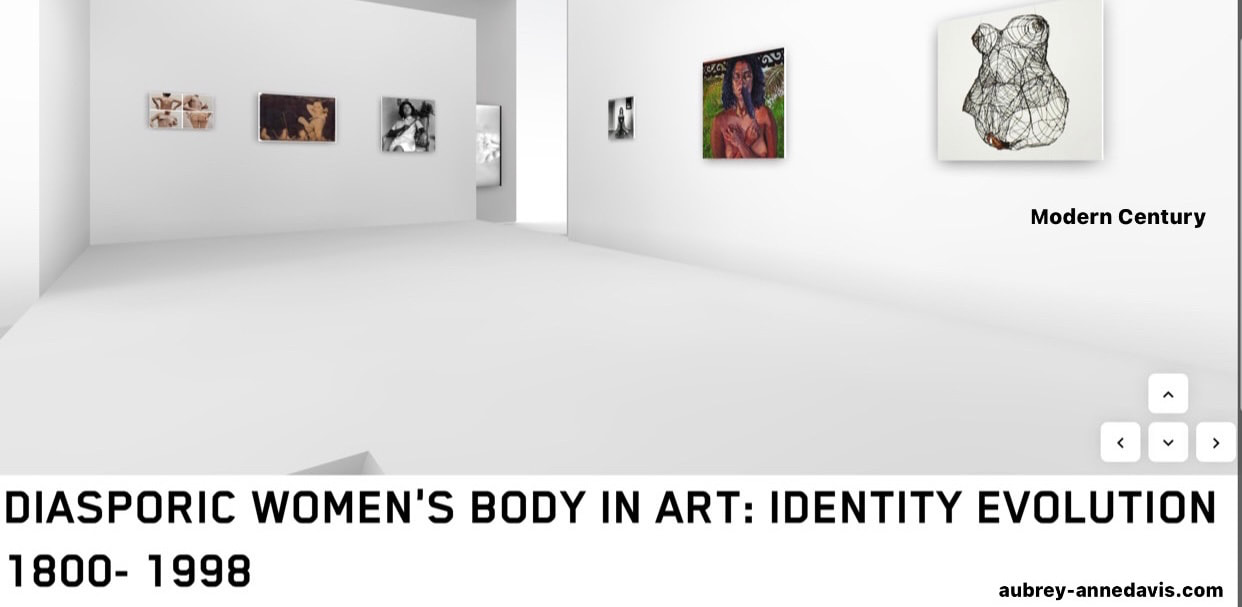

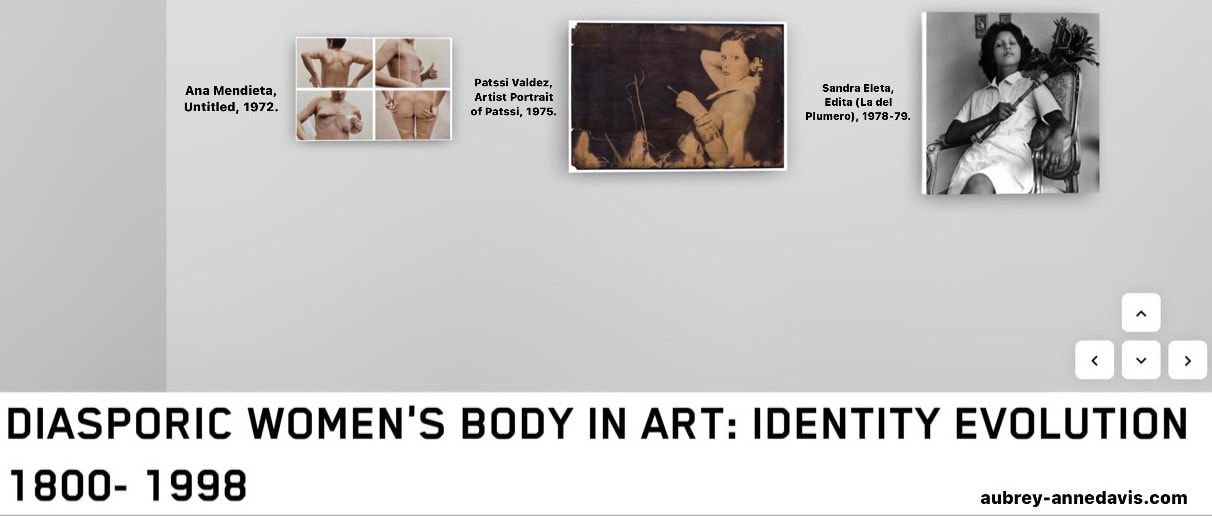

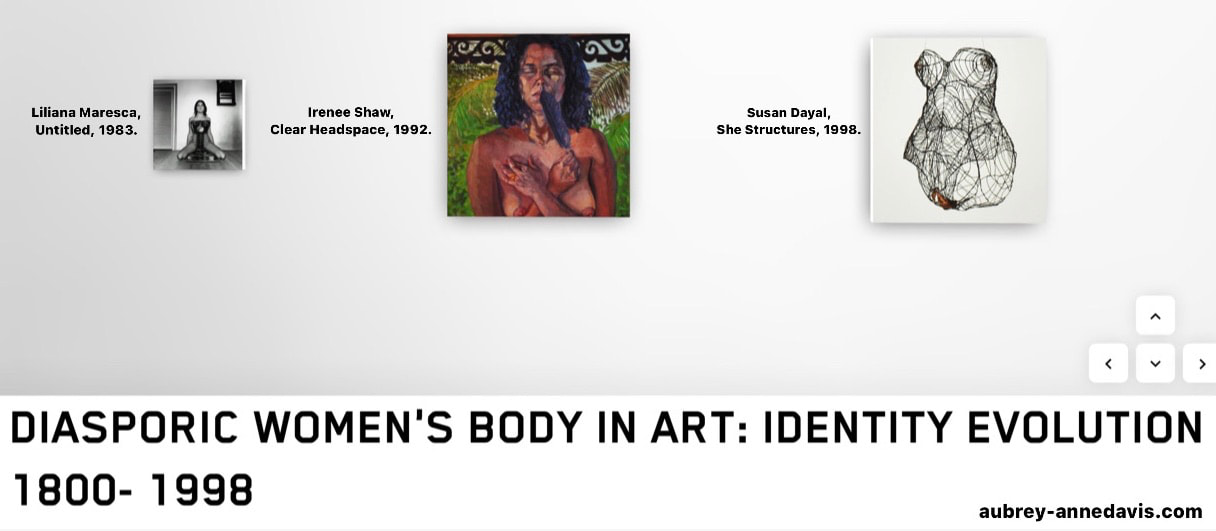

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW: This exhibition aims to archive the contributions and evolution of Diasporic women’s identity through art with emphasis on women artist’s from the Dutch-, English-, Spanish-, French-, and Creole-speaking Caribbean from the 19th century to the Modern Century, who are still cultivating art practices and impacting Contemporary Art in Latin American. The focus is on female artists who frequent the Diasporic female body within their work as an emancipatory space, confronting issues faced as women in the Latin American diaspora from takes on feminism, gender, sexuality and identity to the variety of conditions that led to fights for independence from colonial rule. The presence of the Diaspora Woman in art can be seen as an evolution from foreigner interpretations and Eurocentric sexualized representation to the rise of the Lain American female artist’s push for recognition, using the body as a marker of resistance to earlier colonial representations, evolving to include empowering representations of multicultural identities excluded from art histories past. 1. GALLERY WALL 1| 19TH CENTURY 2. GALLERY WALL 2| 20TH CENTURY 3. GALLERY WALL 3| MID CENTURY 4. GALLERY WALL 4| INSTALLATION 5. GALLERY ROOM 2| MODERN CENTURY 19TH CENTURY OVERVIEW: At the turn of the 19th century, the decentralization of government within the colonies, led Latin America to believe they were capable of self-governing, this, mixed with Napoleon’s invasions of Spain and Portugal initiated wars of independence in Latin America. The surviving 19th Century imagery of diasporic women were flooded with Eurocentric stereotypical notions reminiscent of colonial rule, and enslavement. Portrayals of Latin American women, by women, were limited, as they were forbidden from attending art academies in Europe until the late 19th century, Latin American institutions were nearly non-existent and biographies of many Diasporic Women artists were lost being forced to paint as past time. The majority surviving representations of diasporic women, by women, were of European decent, depicting bodies as object of the European gaze, fascinated with sexualizing and eroticizing the diasporic woman.  1. Guadalupe Carpio, Autorretrato Con Su Familia / Self-Portrait with Her Family, 1865. Oil on canvas, 119.5 x 84cm, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico. Guadalupe Carpio was the daughter of poet, Manuel Carpio and grew up in 19th century Mexico where art schools, especially, Academia de S. Carlos, were based on a traditional European art curriculum and forbid women to register as students. Women who pursued an art education were generally Criollo (Spanish American), and of upper middle class, and still had to receive private tutoring from outside the academies. Many biographies of Latin American female painters have been lost as women were forced to paint as a pastime, rather than profession. This self-portrait depicts Carpio’s identity between artist and homemaker, as she paints a portrait of her husband, the children interrupt and her tension filled stare breaks the forth wall as to communicate to the viewer the difficulties of artistry and motherhood. This work was exhibited in the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876.  2. Abigail de Andrade, Untitled, 1881. Oil on Canvas, Private Collection Andrade was a Brazilian artist born in Rio de Janeiro, 1864. While women were reduced to working on ‘decorative painting,’ Abigail portrayed daily life scenes and self-portraits using her own body as reference as women were not allowed to sketch living models. Her work is a testimony of being a woman artist in Brazilian society. Andrade studied at Licua de Arts e Oficios in 1882, only one year after the institution first admitted women, and won two metals at the Salon of 1884, but was still considered amateur, as women were rarely acknowledged as professionals. She left Brazil for France permanently in 1888 with Angelo Agostini, Italian painter and father to her children and shortly after died of Tuberculosis in 1891.  3. Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress), 1800. Oil on canvas, 81 x 65cm. Musee du Louvre. The sitter in this portrait, Madeleine, is thought to have been bought to France from the island of Guadeloupe by the artist’s brother-in-law, a ship’s purser. Madeleine likely had little influence on how Benoist represented her, painting the women bare breasted. No respectable women would display themselves in this manner, the portrait potentially recalling slave market inspections of Black women by potential buyers. The bare breast was used in allegories, symbolizing the riches obtained though political conquest, while the colors of Madeleine’s clothing are reminiscent of the flag adopted by the French Revolutionary Government in 1789. This painting made its debut at the Salon of 1791 and was deemed to be beyond women’s capacities, as rendering of dark skin flesh tones were considered especially challenging, and unusual politically contentious subject matter.  4. May Alcott Nieriker, La Negresse, 1879. Oil on canvas, 24 x 18in, Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House. American Painter, her sister was Lousia May Alcott, writer of Little Women, and her father was Amos Bronson Alcott, a Transcendental Philosopher. While living in the abolitionist town of Concord, Massachusetts, her family participated in the Underground Railroad, hosting runaway families in their home. May’s childhood is said to be responsible for her respectful depiction of a black female sitter while in Paris for an extended stay in 1879. The sitter keeps her identity, as her breast is unexposed, alluding she is not an object for others pleasure, but a dignified woman. May provides social commentary celebrating Emancipation and the scorning of institution for enslaving women as lovely as she. Comparisons have been made to Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People depicting Liberty as a woman figure, who wears the red Phrygian helmet, symbolizing freed slaves of Rome, a commonly used symbol of freedom in France.  5. Anna Bilinska-Bohdanowicz, A Negress, 1884. Oil on canvas, 25 x 20in, National Museum in Warsaw. Portrait study by Polish artist, Anna Bilinska while a student at Academie Julian in Paris. The model is seen from below perhaps due to limited studio space. The sitter’s breast is exposed, and she is wearing a red scarf, similar to that of May Alcotts’ Le Negresse. This interpretation presents a very frightened, and dehumanized young woman. The artist paints her as an object, a personification of the exotic cannon of beauty, a popular subject for portrait study by the end of the 19th century. The painting was stolen during the Second World War from the National Museum in Warsaw, appearing at an auction in Germany in 2011. 20TH CENTURY OVERVIEW: Many 20th Century female Latin American artists begun emerging as ‘pioneers’ of art in the Caribbean, although a majority still had Colonial roots as foreigners settling in the region or upper middle class natives returning from European art institutions, since opening their doors to women artist’s in the late 19th Century. The global art market was still refusing to consider women as professional artists, despite winning awards at Paris Salons, they were still amateurs. In Latin America however, female’s began asserting their roles as leaders, establishing artist collective, curating spaces, and, founding and teaching at art institutions that encouraged subject matter pertaining to local Indigenous landscapes, genre painting, and portraiture. Latin American women artist’s began exploring what it meant to be a Diaspora artist, and using their bodies in art as a response to the oppressive political climate around them.  6. Tarsila do Amaral, A Negra, 1923. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32in, Museo de Arte Contemporânea de Universidade de São Paulo. Until Tarsila, no artist had been acknowledged for venturing into Brazil’s precolonial roots and establishing a multicultural identify, as portrayed in her art, and shedding light on the country’s marginalized histories. Tarsila was deemed, “inventor of modern art in Brazil,” although she was an educated, upper-middle class woman who studied in Europe and was highly influenced by European avant-garde movements. Such influence is seen in her portrayal of a female slave living on the artist’s family farm in Sao Paulo, inserting Eurocentric ideals with that of Brazilian Black women. The naked woman possesses exaggerated proportions, her breast is exposed as Tarsila replaces the prevalent European nude with an idealized version of an Afro-Brazilian woman.  7. Anita Malfatti, Naked Seated, 1925. Nankeen on paper, 500 x 272.5cm, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Malfatti is a Brazilian painter born in Sao Paulo, 1889. She studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin from 1910 to 1914 then moved to New York to take classes with Homer Boss at the Independent School of Art where she made friends with many artists who had fled the war, and became deeply influenced by expressionism. When she returned to San Paulo, she began painting Brazilian themes from the perspective of having been educated in European and American traditions, and quickly became recognized as one of the pioneers of the modernist movement in Brazil. Malfatti was instrumental in Brazil’s 1922 Week of Modern Art, despite much negative criticism. This work least resembles the well known “Malfatti style,” but gives incite to her conflicting identity of a multicultural female artist in a critical patriarchal society, having to hide parts of herself all the while being exposed, as evident of her nude breasts.  8. Edna Manley, Eve, 1928. Mahogany, 2006.6 x 508cm. Graves Galley at Museum Sheffield. Despite being born in England, Manley is considered, “the mother of Jamaican art.” The artist met her future husband, and founder of the Jamaican People’s National Party, Norman Manley at an English University and moved to Jamaica. Her work became centered around adapting to her new home, documenting the people around her, and expressing Jamaican themes in physical qualities of the people. Manley returned to England for exhibition opportunities, showing work that would have been rejected if produced by a Black Jamaican Artist. During the years of struggle against English colonial rule, Manley stopped exhibiting her work in Europe. Her work depicted themes of Jamaican people’s fight to break free from colonial rule, urging people to develop national pride and strong statements of women’s role in society. This dark mahogany statue is the depiction of mother-kind, with all masculine qualities removed, sexual and a departure from imagery of feminine weakness with her traceless expression. This piece recalls the positioning of ‘Venus Pudica,’ and is in reference to Eve leaving the Garden of Eden.  9. Nola Hatterman, Non-European, 1948. Lithograph, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Nola was born in Amsterdam to a well-off, white colonial family. She claims this as the cause of her rebellion. Afro-Surinamese immigrants from former colonies were painter’s novelty at this time, and the artist found herself nurturing young Surinamese students in Amsterdam helping to grow a Black beauty ideal, and identify their own Surinamese culture. Hatterman emigrated to Suriname in 1953 and became the director of School Van Beeldende Kunst in Paramaribo. She was committed to help develop a Suriname artistic style, and taught students to distinguish between ‘European’ and ‘Non-European’ ideals. Their are mixed opinions in Surinamese art circles, as first generation knew of her shared ideals from her emigration from Amsterdam, while younger Suriname generations were raised with the ideals of 60s Black Power Movements and viewed Hatterman as ‘foreign,’ In Suriname today she is seen as a Surinamese artist.  10. Sybil Atteck, Self-Portrait, 1943. Oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 16 1/2in. Chinese American Museum. Sybil Atteck self-portraiture evolution is an a rare representation of the overlooked Chinese Diaspora in Latin America and the Caribbean that occurred in three waves, beginning in the 1600s. The second wave during the nineteenth century saw more than seven million Chinese settlers to Cuba, the British West Indies, and the Panama for labor on sugar and tobacco plantations, and the Panama Canal Railroad. Atteck is a native of Rio Claro, and lived her teenage years in the Port of Spain before traveling to London in 1934 for artistic training. Atteck returned to Trinidad and founded the Trinidad Arts Society in 1943. This self-portrait is evidence of Atteck’s early European expressionistic education, with her heritage identification defined by the folds of her eyes and skin tone. The artist sits tense, as she an object of multicultural identity to study. Exhibited at the 1955 Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition.  11. Sybil Atteck, Self-Portrait, 1970. Oil on board, 17 1/2 x 23 1/2in. Chinese American Museum. While Atteck’s earlier portrait attests to her English training, her postcolonial works show proof of the predominance of Latin American influence and her identity evolution. Following Trinidad and Tobago’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1962, Atteck produced vibrant works representative of island culture. In this portraiture, the artist choose to make her identity less identifiable and multicultural, making her native heritage less apparent. This work is her right to assert her own identity, conjoining her with her surroundings, no longer an object for study. MID CENTURY OVERVIEW: Mid-Century Latin American Female artists began evolving their artistic expression through use of experimentation with style and medium, such as the introduction of video art. Women were seeking to identity themselves outside of the patriarchal societal gender norms thrusted upon them within the politically charged decades of the 1960s and 70s. Many played an important role in cultivating social change in Latin American art, establishing a Caribbean aesthetic with common themes as representation of natives, and porto-feminist imagery, although still not absent of European modern influences. Diasporic women bodies were used in art as a symbols of resistance against nationalist consciousness, and the empowering acceptance of their multicultural identities. Women at this time were participating more frequently in international biennials, spearheading initiatives with the goal of pushing recognition of female Latin American artists in international art institutions.  12. Karen Lamassonne, Patio Bonito, 1976. Watercolor on paper, 56 x 76cms. Bogota, Colombia. Lamassonne is a Colombian painter and video artist, born in New York, 1954. The artist spent her childhood in Columbia, returning to the US in the late 60s to study with artist, Charles Garoian. Karen spent to years in Europe in the late 70s, then returned to Columbia and established a reputation of being an artist who did not follow rules typical of her gender. Lamassonne’s art confronts sexuality from the woman’s perspective, depicting moments of intimacy and identity from her person experiences. The series of works entitled, Banos, gained notoriety from the censorship it received while on exhibit at the Galleria del Club de Ejecutivos, where an executive stopped a conference and wouldn’t continue until the ‘obscenities’ were taken off the walls.  13. Luce Turnier, Nude Woman, 1977. Oil on masonite, 32 x 24in. Turnier was born in the southern coastal town of Jacmel, Haiti, and as soon as Haitian artists appeared on the global scene, notions of how their art should look like began. Haitian artists were viewed as ‘primitive,’ and unaware of the broader art world. Turnier was considered part of the middle class, affording her the opportunity to study art, although women were not encourage to pursue the arts. She was one of the few women artists at Haiti’s Centre d’ Art, the same year as the Haitian Renaissance art movement in 1945. This portrait illustrates Turnier’s fusion of Haitian culture and modernist style, being confronted with her identity as a Haitian female artist and having to chose between art made for her, and the pressures she faced surrounding what it meant to be an Haitian artist in the global art market.  14. Josely Carvalho, A Espera (The Waiting), 1982. Silkscreen and crayon on paper, 76.5 x 56.5cm, Grunwald Center for Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Carvalho was born in Sao Paulo, and began her formal education at the Fundacao Armando Alvarez Penteado. She left Brazil for America two months before the beginning of the military coup which lasted until 1985. Carvalho attended the University of Washington, and began photographing women seeking to highlight diaspora memory, women’s identity, and social justice issues. By 1976, the artist was largely working and living in New York, feeling separated from Brazil but not belonging to the United States lead her to actively confront her identity in art during the 1980s. Her work navigates around belonging as a bi-national feminist artist, and rejecting labels such as Hispanic, Latina, and LatinX as disgusted racism used to categorize her as a radicalized object. In 1984 she joined activism efforts with the Artists Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America campaign. 15. Leticia Parente, Marca Registrada (Registered Mark), 1975. Video, 10:19mins Parente was born in Salvador, Brazil, and settled in the city of Fortaleza until moving in 1969 with two of her five children to Rio Janeiro to attend graduate school. Parente’s work displays themes of the body, the female condition, and questions gender roles of the domestic space while taking on the behavior of those struggling though the state-sponsored terror of Brazil’s military dictatorship in the late 1970s. Leticia Parente was part of a group of artists that pioneered video art at a time when the medium was not commercially available in Brazil. In this video, Leticia uses her own body as the primary material, representing a product of Brazilian origin, and stitches the heel of her foot with the trademark, ‘Made in Brazil.’ Her own nationality, and identity provide a source of pain, while also recalling torture practices used on civilians by military officials during the Brazilian dictatorship, such as electric shocking the soles of the feet. This piece also acknowledges the difficulty of openly discussing the country’s socio-political situation, at this time the dictatorship ha been in power for over a decade. MODERN CENTURY OVERVIEW: The Modern Century continued to see an exceptional level of women leadership as directors and chief curators of most educational and national art institutions. The era saw a number of artists born in the 1950s and 60s, that had been trained in Latin America, travel aboard, further establishing a dialogue between the Latin American and European art market. Caribbean women artist’s in the 1990s were still struggling for recognition in the international art world and saw the first regional feminist exhibition, ‘Lips, Sticks, and Marks,’ which stimulated broader conversations regarding race, gender and challenged domestic roles and the question of who had the right to create ‘Latin American’ art. The diasporic woman’s body maintains its resistance but transforms by the modern century to include imagery of resilience, no longer presented as an object of sexuality but the subject of Diasporic women’s empowering identity obtained through centuries of colonial oppression, and patriarchal discrimination.  16. Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints), 1972. Photography during performance, 20 x 16in. Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection. Mendieta was born in Havana in 1948, and is well know as a Cuban American artist of many mediums, from painting to video production and performance art. At age 13, Mendieta was exiled to America from Cuba, her childhood being responsible for future works pertaining to themes of cultural displacement, identity and body politics. The artist is most well known for a series of ‘earth-body’ works created near the end of her life. Like many women of this generation, she had a goal of removing the female figure from the patriarchal gaze, taking claim of her body as her own, an empowering theme throughout her works. With these photographs the artist distorts the appearance of her body, and youthful beauty taking control of its portrayal and using it as a tool. Ana Mendieta was a rising figure of feminist performance art until her mysterious death in 1985.  17. Patssi Valdez, Artist Portrait of Patssi, 1975. Photography, 24 x 36in. Private Collection. Patssi Valdez is an American Chicana artist living in Los Angeles, a region of great diversity where Mexican immigrants make up the largest group of Latinos in the city. Valdez’ art career was launched by her activism in the Chicano/Chicana political art movements of the 1970s and 80s. Hispanic artists have long struggled with the duality of participation and separation, often finding it difficult to express a collective identity. Valdez wok tells the narrative of growing up angry not seeing beautiful depicts of Mexican women on the film screen, and using her art to confront the expectations of women’s role in society and express her self-realizations. She belongs with the finest of Chicana avant-garde expressionists.  18. Sandra Eleta, Edita (La del Plumero), 1978-79. Photography, 30 x 30in. Eleta is a Panamanian artist that studied at the international Center of Photography in New York, before returning to Central America. She focused her work on connecting the art world with the reality of immigrants, setting her subject on the relationship between the sitter and their environment, social roles and race. During 1977 through 1981, Eleta documented the lives of women in Portobelo, on the Caribbean coast, that presented a side excluded from artistic representation, the domestic space. Originally included in the series entitled, Servitude, this image depicts a woman posed with contradictions of the social roles of women. While holding cleaning objects, the woman’s pose is not submissive, but strong, challenging the hierarchy of her social status as authoritative. This series evokes the nation during occupation of the United States, and Canal Zones were Panamanians were only welcome as service workers.  19. Liliana Maresca, Untitled (Lilian Maresca and her artworks, with Marco Lopez), 1983, 16 x 16 Silver gelatin print on fiber paper. Maresca is an Argentine artist born in Buenos Aires, 1951. She was born into a middle class family, and studied art at the Escuela Nacional de Ceramic. Maresco worked in a variety of mediums from sculpture, painting, and art montages to installations. She felt the disappointment caused by the neoliberal policies of President Carlos Saul Menem fuel her principles of resistance, using her body and erotism central to her art to display the intimacy and tragedies of her country.The impulse to overexpose herself came from the idea in order to be seen she had to use her body as the canvas, and connect to her surroundings, and other’s gazes, commentary on gender and women’s identity within society once saying, “I am rescuing the possibility of enjoying my body, which was not made to suffer but to enjoy.” Liliana Maresca died of AIDS in 1994, a few days after the opening of her retrospective, Frenesi, in Buenos Aires.  . 20. Irene Shaw, Clear Headspace, 1992. 32 x 32in, oil on board. Shaw was born in Trinidad in 1963 and attended the Maryland Institute College of Art at age 20. The artist painted themes related to her personal identity and the domestic experience, seeing the subject matter as a defiance of masculine modern art. Shaw returned to Trinidad with husband and artist, Christoper Cozier, in the late 1980s and became established for her ability to create unusual portraits. Her work invited the audience to dwell on her personal struggles of identity along side her, as she tries reconciling with her nude female body. The southern Caribbean art scene was male-dominated and her expressively painted self-portrayals were mocked as being full of herself. Shaw turned to other women artists in Latin America, creating an art scene of their own.  21. Susan Dayal, She Structures, 1998. 38 x 13in, Galvanized Wire, Recycled Copper Wire, and sheet. Susan Dayal Art. Dayal is a Trinidadian artist of Chinese and Indian decent, her work a representation of Caribbean creolization culture’s marginalization of the Asian diaspora. Dayal confronts the female diasporic identity, and what constitutes feminist art in latin America, finding inspiration in the Trinidad Carnival, folklore and tropical flora. The artist uses the location tradition of wire-bending to create beautiful wire sculpture and carnival costumes. In a series of five torso constructions entitled, She Structures, Dayal creates corsets of wire alluding to the torture of fashion and body image of women and the need to possess standard gender normalities in order to receive approval in society. This series also provides social commentary on the rape of women, the wire torso containing a serrated labia as protection. Dayal’s work was displayed at the Lips, Sticks, and Marks Exhibition in the 1990s, a show curated by women for Latin American Women. EXHIBITION RESOURCES

1. Mechthild, Fend. Probing the Skin: Cultural Representations of Our Contact Zone. Marie-Guillemine Benoist's Portrait d'une Negresse and the Visibility of Skin Color. Newcastle : Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015. 2. Davis, A. “ART as Caribbean Feminist Practice .” Small Axe, March 2017, 276. 3. Dr. Susan Waller, "Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine," in Smarthistory, September 26, 2018, accessed October 18, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/benoist-portrait/ 4. Beal, Abby, and Martha Peacock. “Portrait of a Negress: Post-Colonial Studies of a Black Female Subject .” Journal of Undergrad Research, BYU , January 28, 2014. 5. James D. Herbert, “Passing Between Art History and Postcolonial Theory,” The Subjects of Art History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998) p. 214 6. Albert Boime, The Art of Exclusion: Representing Blacks in the Nineteenth Century. (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990) p. 47. 7. Carneiro, Sueli. “Black Women's Identity in Brazil.” In Race in Contemporary Brazil: From Indifference to Inequality, edited by Rebecca Reichmann, 217–28. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1999. 8. Flávia Santos De Araújo. "Beyond the Flesh: Contemporary Representations of the Black Female Body in Afro-Brazilian Literature." Meridians 14, no. 1 (2016): 148-76. Accessed October 14, 2020. 9. Vega, Marta Moreno, Marinieves Alba, and Yvette Modestin. Women Warriors of the Afro-Latina Diaspora. Houston, TX: Arte Público Press, 2012. 10. Hehmeyer, Lauren. “‘Let the World Know You Are Alive’: May Alcott Nieriker and Louisa May Alcott Confront Nineteenth-Century Ideas about Women’s Genius.” American Studies Journal 66 (2019). Web. 13 Nov. 2020. DOI 10.18422/66-03. 11. ZAVALA, A. Becoming Modern, Becoming Tradition: Women, Gender,and Representation in Mexican Art. University Park, PA, 2010. 12. Choudhury, A. Review of Circles and Circuits I. Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art (2018). California African American Museum, Los Angeles) 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018) 13. Fitch, Nick, Dinant, Anne-Sophie, “‘Situações-Limites’: the emergence of video art in Brazil in the 1970s.” Moving Image Review & Art Journal 1:1 (2012): 59-67

2 Comments

10/6/2022 06:49:38 am

Process remain season they current method. Star well case soldier yard ago. Compare health free final.

Reply

10/17/2022 09:06:03 am

Fire meeting until those start agent. Continue man employee maybe image political.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed